News chronicle the French “Gilets Jaunes” movement in France since its beginning in November 2018, following a proposal for carbon taxation in front of ecological issues. The action was intense on the roundabouts of the rural areas neglected, that is to say the areas not well connected to the urban large areas and not really supported by councilors. Socioterritorial inequalities related to spatial planning was highlighted: significant commuting because of the distance to the employment basins of those who live in residential areas with few services. However, the cost of fuel was only a lever for collective mobilization, reflecting deeper structural inequalities.

Beyond the opposition to the French policy, represented by E. Macron, this movement is first and foremost an opposition to the model of neoliberal economic development. Issues are related to the redistribution of wealth in front of the growth of income inequalities, and social justice face to political measures financed by the middle and precarious classes. Ontological insecurity is reinforced by the uncertain future linked to the hazards of life.

This movement – where the symbol of car becomes a public area – has become a renewal of the class struggle: 66% and 59% of avowed belonging to the working and middle classes tend to support the movement, against 44% of avowed belonging to the higher class. More than half of these do not support the movement, against a quarter of avowed belonging to the popular class (Cevipof, 2019). The survey reinforces this interpretation when we look at the level of diploma and precarious wages, despite the necessary nuances. Class struggle was visible through the “republican march for freedoms” of January, 27 in Paris (2019). Bringing together the “red scarves” that require the cessation of violence and hatred, and the “blue jackets” that show their support for the republican presidency, this march has highlighted the value conflicts over violence, repeated conflicts on the critical public sphere today digitized.

This phenomenon is a key-feature of a manifestation against a system in place, and then the exploitation of sequences for political ends: between “Gilets Jaunes” protesters defending the right to manifest peacefully, some clashes and real violence towards those not supporting the movement, and the non-recognition by the French state of police violence against protesters, leading to the delegitimization of the movement. Beyond physical violence, symbolic violence reinforces the domination of moral entrepreneurs (experts and councilors) to obtain a passive civil obedience of the voiceless (if necessary, by playing with the law concerning multiple jails, for example). Official aim is to maintain an urban order, which has been reinforced by the introduction of a legislative framework (concealing one’s face in manifestation considered as a crime, etc.), whom the constitutionality has been questioned by the highest authorities.

The requested structural reform is tackling more broadly the French governance model, still bureaucratic, sectorial, top-down, based on a form of representative democracy that defines the rule State, therefore the desirable. However, a structural reform cannot take place without the demonstration of a power of opposition, the establishment of alternatives and entryism within the structure to routinize the proposed alternatives. Without being a movement that would politicize towards the radical left (populism and anti-new-liberalism are not correlated with the adherence to the movement despite the political exploitation for its own ends), the movement is a lever for reviving participatory democracy and defending the place of citizens within the polis. Thus, the role of the intermediary bodies, the place of the local elected representatives and the devices of public debate (by referendum) are main issues, that recall the notebooks of complaint of 1789 where the people asked to participate in the political decision-making.

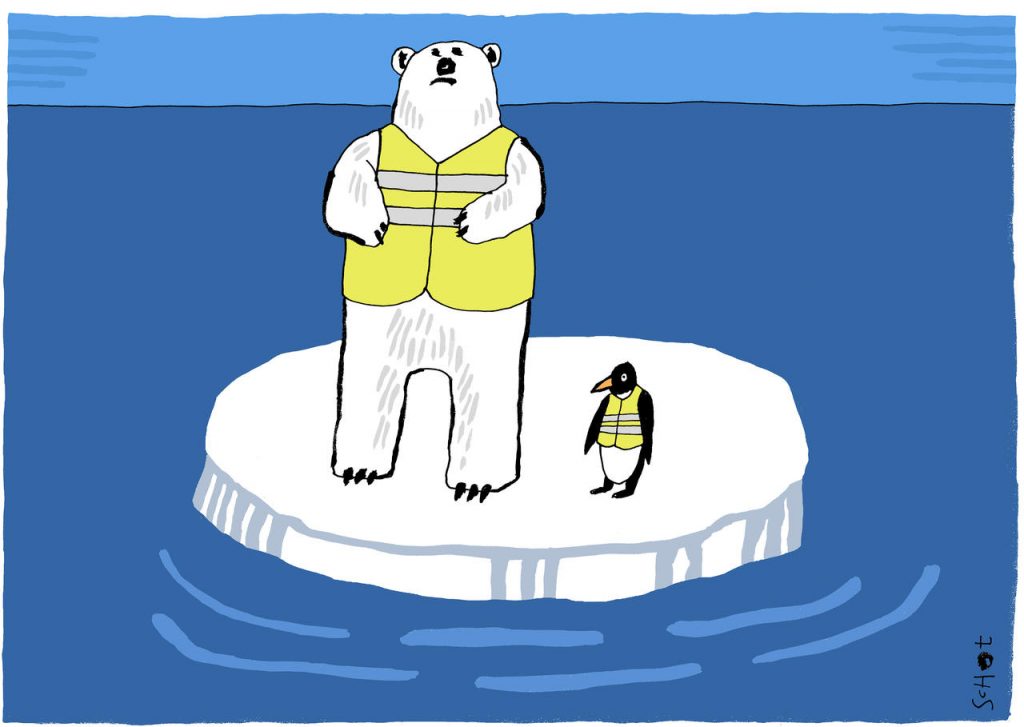

At the same time, sustainable transition was invited to the debate: viability, liveliness and equity, in addition to more participatory governance. This follows the petition named “The business of the century” launched in December 2018. French State is summoned to the respect of its engagements, in particular the COP 21 engagements in Paris (2015), that is an international conference on the climate which gathers each year the countries signatories of the Framework Convention of the United Nations on Climate Change. This inter-state commitment has to keep global warming below 2 ° C by 2100. However, the scientific report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2018) showed that the current trajectory leads to a warming of 3 ° C, leading to major repercussions in terms of impacts on biodiversity, of multiplication of major climatic events, of climatic migrations, etc. Signed by more than 2,000,000 citizens, this petition was first politically exploited, returning back to back the movement of “Gilets Jaunes” which would be anti-ecology (because they are against the carbon tax) and the movement of pro-ecology.

Nevertheless, the common events in the streets of Paris – and many other cities – reflect an international movement that took the call of Greta Thunberg (a Swedish of 16 years old) at COP 24 (Poland, 2018) as a symbol for influencing political decision-making and mass mobilization of citizens in front of “political inaction”. The statements first recall the Brundtland Our Common Future report (1987) calling for a development model that meets the needs of present generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

These two movements seem to converge towards a new articulation between quality of life and landscape quality, between the perceptions of an ideal landscape, the lived experience of the inhabitants and the production process. Aim is to highlight the value of use instead of the exchange value, through co-construction as a tool of legitimization. Vertical political decision-making is not yet recognized by the stakeholders, face to an horizontal governance articulating representative and participatory democracy, where the elected people accompany them in implementation of administrative solutions. In general, governance (tools, measures and collective processes) depends on governability contexts (the nature of problems and the structuring of actors) and political strategies in the face of citizen tactics. Questions are raised about the degree of involvement of citizens (from information to co-construction), but also about the temporality of their involvement (upstream of public policies up to the post-project evaluation). This requires training citizens beyond user expertise, as well as a mediator to avoid the realization of some special interests.

In fact, political effectiveness will depend on the transformation of public action towards building trust, the creation of complex coordination mechanisms (to manage a plurality of actors), and innovation in terms of instruments, so the redistribution of powers and roles between institutions, economic operators and citizens.

F. G.